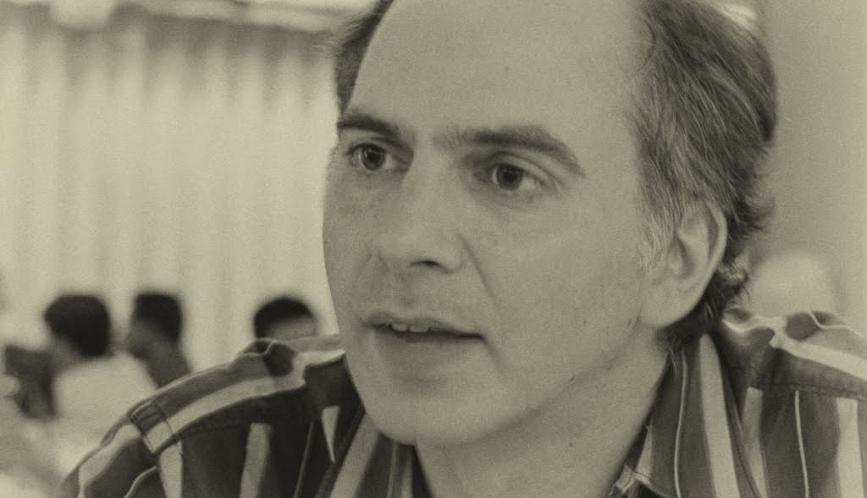

Anthony Laden, an MIP network member, is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Illinois Chicago, and is also Associate Director of the Center for Ethics and Education. Laden works in moral and political philosophy, where his research focuses on reasoning, democratic theory, feminism, the politics of identity, and the philosophy of education. He is the author of Reasoning: A Social Picture (Oxford, 2012), Reasonably Radical: Deliberative Liberalism and the Politics of Identity (Cornell, 2001), and is the co-editor (with David Owen) of Multiculturalism and Political Theory (Cambridge, 2007).

Describe your area of study and how it relates to current policy discussions surrounding inequality.

I work in moral, social and political philosophy and the philosophy of education. I am currently at work on a book on democracy that traces out some of the implications of treating democracy not as a system of rules, procedures and institutions for making legitimate collective decisions, but as a way of living together wherein we work out together the terms on which we live together. This approach helps to focus attention on what I call the practice of equality: how and to what extent we treat each other as equals, as full co-authors with us of our lives together. Practices of equality (and inequality) show themselves in whether we hold certain people beneath contempt, or not worth taking seriously, and whether we understand and act as if their lives matter. They can be supported or hindered by how we distribute resources and political power and influence, but they are not exhausted by those issues. Sometimes they are treated under the umbrella of respect or recognition, but they are often not thought to be central to the sorts of questions of equality that drive lots of policy and quantitative social science.

What areas in the study of inequality are most in need of new research?

Following on my answer above, I would welcome research that integrates concerns with practices of equality into more quantitative measures of inequality. I also suspect there is more interesting work to be done of the differences between the inequalities that accrue to the very top of the income distribution (the 1% and above) and those that accrue to a wider swatch of the top (the top 20%). Richard Reeves work on opportunity hoarding is helpful here. Understanding the different modalities that preserve these forms of inequality and the harms they inflict on justice would help us guide policies that genuinely help those in the bottom 80%, and not merely spread the wealth of the 1% to those in the top 20%. Finally, there is an interesting range of questions concerning how inequality is sustained not so much by what we do or support, but what we don’t notice or concern ourselves with. Some of this is captured in work in critical race theory around “white ignorance” but I suspect there are also wider issues to be explored here.

What advice do you have for emerging scholars in your field?

Pick topics you are genuinely interested in. As one of my teachers told me, “trust in the integrity of your own mind,” i.e. trust that the questions that interest you will eventually come to be related in interesting ways. And finally, seek out as many inter-disciplinary tables to sit at as you can and use the experience to figure out what you, given your own disciplinary training, can bring to such tables. That is one of the best ways to gain an understanding of what you think you are doing when you are working in your own discipline. Understanding that will help you make inter-disciplinary contributions, but will also give your work within your discipline a clear voice and direction.